Legislatures and hospitals around the country have tightened emergency room prescribing guidelines for opioids to curb the addiction epidemic, but a new USC study shows that approach diverts attention from the main sources of prescription painkillers.

Overall opioid prescribing skyrocketed 471 percent from 1996 to 2012, according to the study by USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics and the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

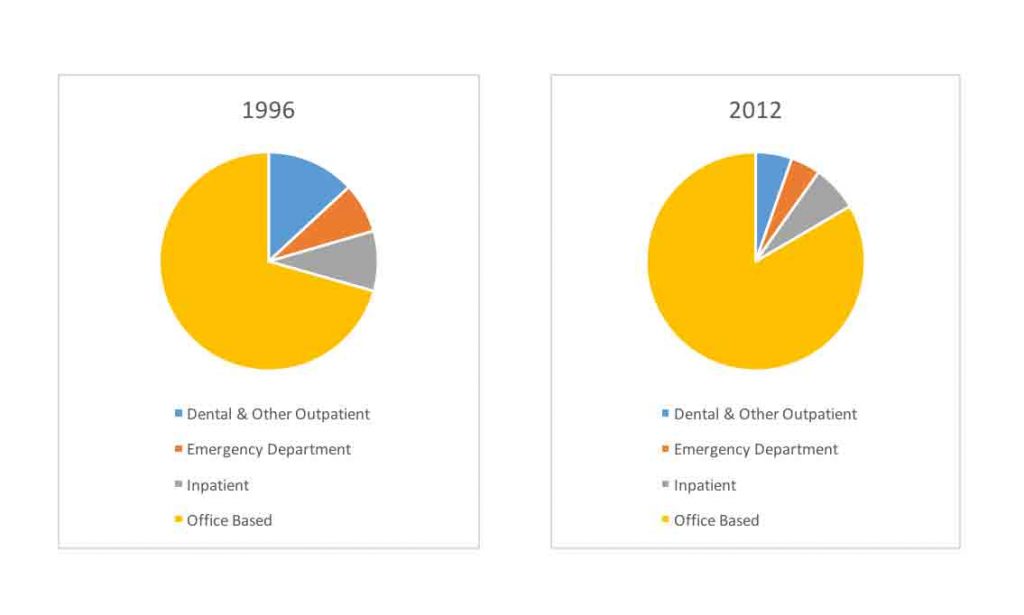

But the share of opioids prescribed from emergency departments was small and declined during that 17-year period, from 7.4 percent to 4.4 percent. The share of opioids prescribed from doctor’s offices was much larger and actually increased during that period, to 83 percent from 71 percent.

“One hypothesis has been that the emergency room is a recurrent site of care and that patients could be going from ER to ER to obtain multiple prescriptions to support their addiction,” said Sarah Axeen, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the Keck School of Medicine and researcher at the USC Schaeffer Center who led the study.

“But our analysis shows that emergency rooms account for a very small share of all prescribed opioids. In fact, doctor’s offices are the source of many more of these drugs.”

Where are opioids prescribed?

The researchers said emergency departments have become one of the most tightly regulated areas for prescription opioids in the health system. On average, though, 44 percent of the average patient’s prescription opioids were prescribed from a doctor’s office in an outpatient setting, 26 percent from dental offices and other outpatient sites, 16 percent from emergency departments and 14 percent from inpatient hospital settings.

The study published Jan. 16 in the journal Annals of Emergency Medicine comes just as a growing number of states have tightened restrictions on opioid prescriptions with the hope of curbing addiction and reducing the number of opioid-related deaths.

The data analyzed for the study were from the annual, nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey of patients. The survey is conducted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

A look in the mirror

Doctors and other providers are wrestling with the scope of the opioid epidemic, and with the acknowledgment that they contributed to it, said Michael Menchine, a study co-author and an associate professor of clinical emergency medicine at the Keck School of Medicine.

“From the 1990s to at least 2013, we had convinced ourselves that prescribing opioids was a fine thing to do” for patients in chronic pain, Menchine said. “It is hard to look in the mirror years later and say 2 million people might be dependent on opioids because of this sort of practice.”

Opioids killed more than 42,000 Americans in 2016 — the most of any year on record, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At least 40 percent of all opioid overdoses involve a prescription.

High-risk opioid users — those with the highest use — represent the top 5 percent of annual opioid consumption. The study showed that a high-risk user obtains just 2.4 percent of his or her opioids from an emergency department prescription, but 87.8 percent from a doctor’s office. Furthermore, more than 80 percent of the chronic and high-strength dosage prescriptions were from office settings.

Focus also on treatment

Study co-author Seth Seabury, the director of the Keck-Schaeffer Initiative for Population Health, said policymakers and providers have good intentions but over-restrictive prescription policies for emergency rooms are not targeting the main source.

“We are not saying these policies are bad,” Seabury said. “What our findings suggest is that they should really be focusing these policies on other places in the system.”

Policies that just restrict opioid prescriptions do not address the growing need for treatment for people in the throes of addiction. The health system could benefit from a more holistic approach by putting greater focus on substance abuse treatment, starting in the emergency room, Menchine said.“We are not saying these policies are bad,” Seabury said. “What our findings suggest is that they should really be focusing these policies on other places in the system.”

“I want to be there for my patients and if they have substance abuse problems, I want to be able to address it in the best way I can,” Menchine said. “Too often people think the solution is to simply say we can no longer prescribe opioids. For me, the solution is to say: It looks to me like you have a problem with opioid addiction and here are the options available so you can address it.”

The study was funded by a grant from the Emergency Medicine Foundation to Menchine and Seabury.