Dementia diagnoses increased after Medicare Advantage (MA) began calculating plan payments to account for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, according to a recent USC study.

In 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reintroduced risk adjustment – a methodology used to estimate the cost to treat a patient – for dementia. The change gives MA plans, the private plan alternative to traditional Medicare, financial incentive to improve dementia detection, as plans are paid more for patients with more serious health problems than healthier patients. The more diagnoses a beneficiary has, the higher their risk score and the more Medicare pays the plan, raising concern that some MA plans might “upcode” or over-diagnosis as a result.

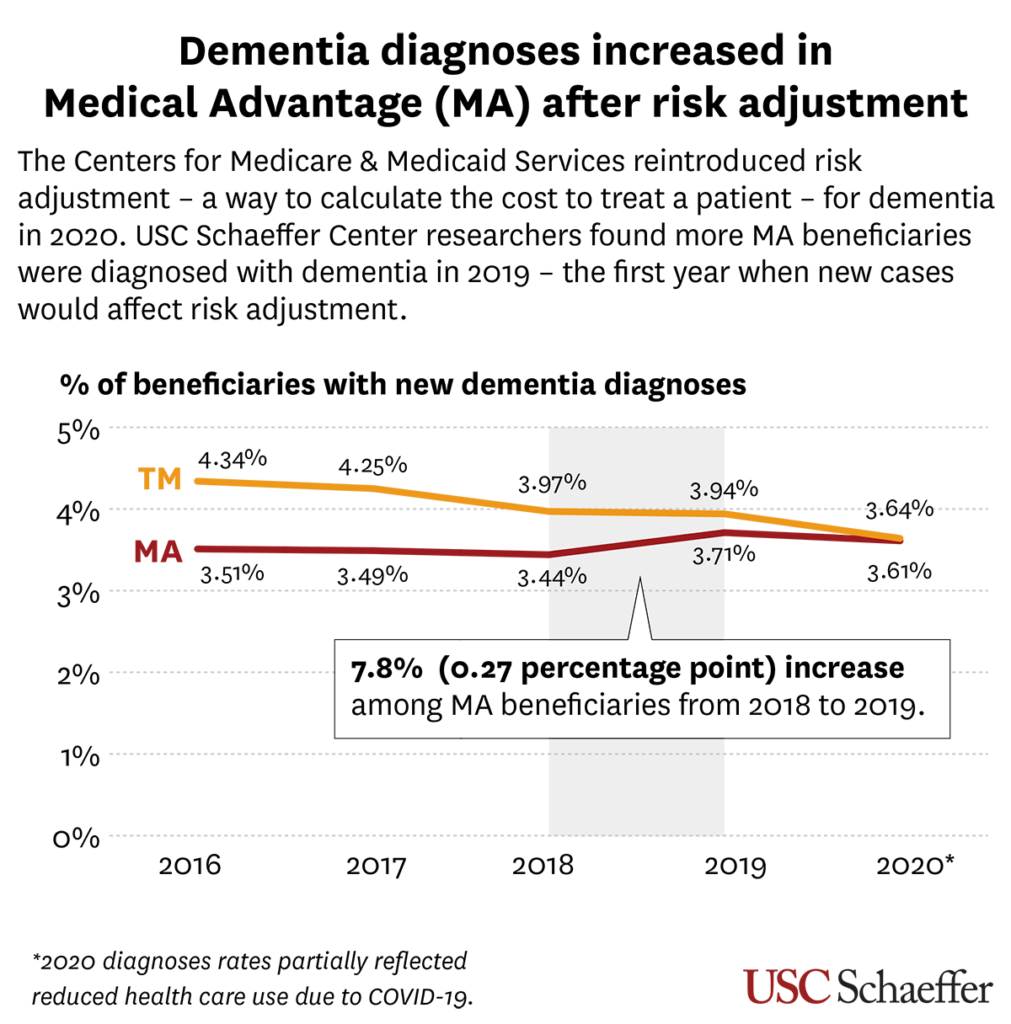

While the total number of Americans with dementia is increasing as the population grows older, age-adjusted rates of new dementia diagnoses (incidence) have been declining over the past decade. At the same time, an increasing number of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolling in Medicare Advantage plans, changing the demographic composition of the program. The study adjusted for compositional changes over time to isolate the effect of risk adjustment and compared the time trend in dementia diagnoses in MA relative to traditional Medicare (TM), where reimbursement levels were unchanged.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, found that a higher fraction of MA beneficiaries were diagnosed with dementia in 2019 – the first year when new cases would affect risk adjustment.

More specifically, the percentage of MA beneficiaries who were diagnosed with dementia increased by 7.8% between 2018 and 2019, according to research from the USC Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The uptick broke a trend of unchanged rates of new dementia diagnoses in MA over the prior three years and modest declines in TM.

One of the challenges to treating and supporting persons with Alzheimer’s and related dementias is that many people with the condition go undetected, said study lead author Julie M. Zissimopoulos, co-director of the Schaeffer Center’s Aging and Cognition research program and professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

Previous research from the Schaeffer Center found that about 20% of older Americans with dementia may be undiagnosed. Their research has also found that there was a higher rate of diagnosed dementia among enrollees in traditional Medicare compared to otherwise similar enrollees in MA.

“We’re entering a new era for disease modifying treatments for Alzheimer’s, and many of these treatments are targeted towards early stage disease,” Zissimopoulos said. “That means people need to get detected and diagnosed early in disease stage to be eligible for the treatments that may benefit them.”

Another challenge is the racial disparities in dementia diagnoses. Studies have shown, for example, that Black people are at higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, yet are less likely to be diagnosed with the conditions than white people.

“Medicare Advantage plans enroll a disproportionate share of beneficiaries who are racial and ethnic minorities,” said study co-author Mireille Jacobson, co-director of the Schaeffer Center’s Aging and Cognition program and associate professor at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. To the extent the changes reflect new diagnoses, this policy has the potential to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in ADRD diagnosis.”

Researchers examined CMS-provided data from all Medicare beneficiaries through 2020. More recent data is needed to see if the trend continues since the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the healthcare system.

The big question that comes from the study’s findings is whether risk adjustment is leading to better dementia detection or inappropriate “upcoding” or over-diagnosis.

“Is this financial incentive encouraging better dementia detection? If so, then the financial incentive is probably working in a positive direction – diagnosing persons with dementia who may have been previously overlooked,” Zissimopoulos said. “The other side of that is the extent to which this reflects upcoding – the practice of over identifying disease and diagnoses because of the financial incentive.”

More about this study:

In addition to Zissimopoulos and Jacobson, the study was also co-authored by Geoffrey Joyce, Health Policy Director at the Schaeffer Center and associate professor at the Alfred D. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Services. The Schaeffer Center is a partnership between the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy and the Alfred D. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Services.

This study was funded by grant P30AG066589 from the National Institute on Aging.

Read more at the Schaeffer Center.